By Andrew Kemp

By Andrew Kemp

Contributing Writer

TICKLED, now playing in Atlanta movie theaters, is a whodunit at heart. New Zealand journalist David Farrier had hoped to write a short article about some videos he found online depicting something called Competitive Endurance Tickling. He couldn’t have known that the response to his request for an interview would send him on a multi-year journey to uncover a dark underbelly to this seemingly good-natured sport and, perhaps, a real-life monster.

ATLRetro talked with Farrier about the making of this insane little film, improvisational journalism, fetish culture, and how it felt when he first realized what he was getting into.

Note: the reception on our phone call was patchy, but we worked around it for the most part.

You can read my review of TICKLED here.

ATLRetro: First of all, I really loved the film. I’ve never been so on the edge of my seat watching a conversation outside a coffee shop.

David Farrier: [laughs] I know, I know. And like the world’s [unintelligible] car chase.

Right. I think I even said out loud in my chair when it happened, “we are having a car chase right now.”

DF: [laughs]

It was just very surprising. So, obviously it’s difficult to ask directly about the fallout over the film without spoiling it. For instance, the event that happened at the LA premiere.

Yeah, yeah. On that I’d just say that, you know, it’s been a pretty interesting time. People from, I mean the movie is about Jane O’Brien Media, and it doesn’t paint them in a particularly great light, and at one of our premieres we had some key players from the film turn up. And at the end of this film, during the Q&A, [unintelligible] with more legal action. That’s been going on through the whole process.

When I was done watching the film, I didn’t get the feeling that the story was finished. It felt like some things are just beginning. What’s it been like promoting a finished film when it’s still unfolding day to day?

When I was done watching the film, I didn’t get the feeling that the story was finished. It felt like some things are just beginning. What’s it been like promoting a finished film when it’s still unfolding day to day?

It’s difficult mainly because that people we want people to see the documentary without knowing too much, and when people see this documentary, when they’re coming out to a screening, that’s out there now, so we have to talk about it. [unintelligible] people to not watch the trailer, not read a review, watch the movie, and get into all that afterwards. The story is very active, as you say, you know. We showed everything in the film that we wanted to show at the time, but since the company is still active, of course, they’re going to push back after the film’s out, so we just have to keep on going.

When you sent that first email off at the very beginning of the film, things quickly went off the rail. I’m curious to know what kind of story you thought you were going to make before that first response. Where were you headed?

Yeah, I mean, I was just looking to generate a one-and-a-half minute story about, you know, here’s this crazy sport about competitive endurance tickling. And I wanted to talk to a competitor and I wanted to talk to the organizer. And get some shots of the event and maybe an interview with the organizer and an interview with the New Zealand competitor. But, you know, that first response that was very aggressive about telling me not to do the story, you know, that changed all that. I didn’t have my nice one-and-a-half minute story, it turned into something completely different.

Right, I get the impression that if you had gotten an answer that was just “no, we’re not interested,” then all of this that has come to light wouldn’t have come to light.

Oh, totally. [unintelligible] I would have forgotten about it and moved on. I was in a quick turnaround situation, so each day I had to turn in a story. So I didn’t have time to investigate, I had to move on to the next thing. Had it been a more measured response, there wouldn’t have been a documentary.

What was the first moment where this started to get too real? Was there ever a moment where you were scared?

There were lots of moments, I mean I was apprehensive when I went to the airport, you know, they sent representatives and I was going to have a meeting. And there was the time I spent in America, approaching people on the street. So approaching them I found nerve-wracking, but [co-director] Dylan and I, we were in this together from the start, you know. We came across this crazy thing. We both got warned early on by this company that we expect legal action to happen, so we were united in that, I suppose. So if we hadn’t had each other, I probably would have run away from the whole thing.

Yeah, you guys seem to have a good working relationship. It seemed that there were moments where each of you had a choice of whether to continue or stop.

Yeah, you guys seem to have a good working relationship. It seemed that there were moments where each of you had a choice of whether to continue or stop.

There were lots of discussions. It was like that the whole way through. If one of us was coming under threats or attacks, you know, we’d talk to the other person and share what we’re going through. We’d share everything in the process, right? In a practical sense, it was really great having someone else in this with me.

You’ve mentioned in interviews that you don’t have a background necessarily in investigative journalism.

No, no.

When you were doing this investigation, did you sit down and come up with a step by step plan, or were you kind of improvising as you went along?

I mean, the story happened really quickly. We did the Kickstarter campaign so we could start shooting it really quickly, and we did that initial shoot, and then we came back realizing the story was of a scope, was like, bigger. And we had a lot of time to prep and prepare for the second shoot, and I write entertainment, I was in the newsroom among all the hard current affairs reporters, and I always kind of admired what they were doing. [call completely breaks up at this point]

I think you actually broke up a little bit right there.

In the news room, I did, like entertainment, but I was sitting next to some really hardened current affairs reporters, so I absorbed a lot of what their techniques were. But really, it was just a lot of research, a lot of planning, and just being super aware of what could happen, what could not happen in any kind of situation, so I could react accordingly. So really just lots, and lots, and lots of preparation.

I’ve seen the film and I think you do a very good job of avoiding one of the concerns you might have going in, that this was going to turn into “fetish shaming.” I’m curious when you’re developing your approach on the film, was that something you were aware of, did you have to take pains to make sure that didn’t happen?

Oh, yeah, right from the beginning. Right from the beginning, we were super aware that we didn’t want to paint the fetish community with the same brush. It was the idea that, yes, there’s some bad stuff going on, but it’s less about the fetish and more about the harassment going on around it. One of the first people who reached out to us and supported our Kickstarter was Richard Ivey, who was filming in the fetish [community] and his whole career was built around it. And he came on board with the same concerns, like “I hope you’re not going to make a film that paints us,” you know, “in a negative light.” Yeah, it was right from the beginning that we wanted to make it super clear, and make it clear in the movie, you can be into tickling, there’s nothing wrong with that. I mean, that’s great, it should be celebrated, but, you know, the dark world that we stumbled onto was somehow almost separate to the tickling.

Right, in the video of the LA premiere, there was a debate going back and forth between you and one of the people involved about whether the tickling videos are pornographic.

Right, in the video of the LA premiere, there was a debate going back and forth between you and one of the people involved about whether the tickling videos are pornographic.

Yeah, that was one of the rather obscure arguments. [laughs]

The idea that they’re just pornography with clothes. I’m just curious about that distinction. Why does that distinction need to get made by them that they aren’t?

That’s a whole other side of it…but that’s not what the film is actually about, and what the problem is. He claims that he doesn’t make fetish content. Now I would argue that Jane O’Brien Media is making, [are] not necessarily pornographic, but certainly, what’s the word? Erotic, and it’s really in the debate about what is erotica versus what is pornography. But, you know, anything can be erotica. If that happens to be young, good-looking, athletic men in sports gear tickling each other, that’s not all that surprising.

I have a question about the decision, and this was probably a conversation in the editing room, but the decision to show the tickling videos unblurred, showing all the faces of the people participating in them unblurred.

Yeah, the understanding was that we [had] many tickling videos, [but] we wanted to not focus on the tickling videos to an excessive degree. Because some of the people in the tickling videos, you know, we had to talk them about it. But all the videos were already online en masse, like they’re already out there. And our film explains why they’re in it. So while they’re online, hour-long tickling videos, the film provides context for why they’re there and how the people got there. I mean, I don’t want to give spoilers, but it kind of contextualized what was going on. The videos that were no longer online and no longer out there, we blurred those ones. Some of these videos were over a decade old and we didn’t want to bring those back for people, and also we didn’t know who was in them, so we thought about that a lot in the editing room.

To me, I find it an interesting dichotomy between the tickling videos as kind of a metaphor for everything else that’s going on. Somebody sitting on top of somebody else, and dominating them. Whether that’s physically happening in a video, or metaphorically happening in everything else.

Completely, oh yeah, definitely.

So the videos themselves are harmless and the [surrounding] behavior is bad, or are these videos themselves exploitative?

No, the videos… the people who were in those videos, if they knew who was behind it and why it was being created, if they knew all of that and kept doing them, that would be fine. What makes it exploitative is that they don’t know—the people that I’ve spoken to—they don’t know what those videos are for. And I think that’s wrong. In a nutshell, there’s nothing wrong with making tickling videos as long as you know who they’re for and where they’re going and what they’re going to be used for, etc. It becomes problematic when you don’t know the answers to those questions.

TICKLED is now playing at Landmark Midtown Art Cinema. Click here for showtimes.

Andrew Kemp is a screenwriter and game designer who started talking about movies in 1984 and got stuck that way. He can be seen around town wherever there are movies, cheap beer and little else.

THE ZOOKEEPER’S WIFE (2017); Dir. Niki Caro; Starring Jessica Chastain, Daniel Bruhl, Johan Heldenbergh; Trailer here.

THE ZOOKEEPER’S WIFE (2017); Dir. Niki Caro; Starring Jessica Chastain, Daniel Bruhl, Johan Heldenbergh; Trailer here.

HIGH-RISE (2015); Dir. Ben Wheatley; Starring Tom Hiddleston, Sienna Miller, Luke Evans, Jeremy Irons, Elisabeth Moss; Opens Friday, May 13 at

HIGH-RISE (2015); Dir. Ben Wheatley; Starring Tom Hiddleston, Sienna Miller, Luke Evans, Jeremy Irons, Elisabeth Moss; Opens Friday, May 13 at  You may be asking why the residents don’t just leave the building as it stops sustaining them? This is where we approach the novel’s unfilmable reputation. Those looking for a clean narrative like LORD OF THE FLIES or even

You may be asking why the residents don’t just leave the building as it stops sustaining them? This is where we approach the novel’s unfilmable reputation. Those looking for a clean narrative like LORD OF THE FLIES or even  Director Ben Wheatley has developed a reputation for off-center oddities, including 2013’s

Director Ben Wheatley has developed a reputation for off-center oddities, including 2013’s  SIREN (2016); Dir. Gregg Bishop; Starring Hannah Fierman, Chase Williamson; Justin Welborn; IMDB link

SIREN (2016); Dir. Gregg Bishop; Starring Hannah Fierman, Chase Williamson; Justin Welborn; IMDB link

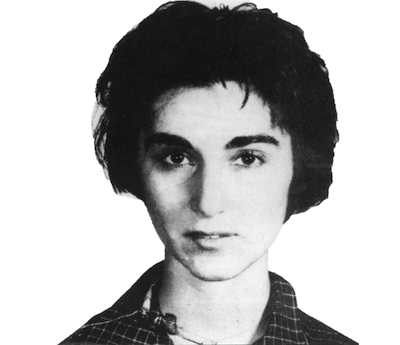

The center of the film, however, remains Bill Genovese, who narrates and drives the action as he pieces together the truth, which is not so simple a thing as the ‘facts.’ He doesn’t only want to know what happened, but why, and even how. Confined to a wheelchair due to his war injuries, Genovese is a nonetheless imposing figure as he confronts reporters, lawyers, and even the aging witnesses in an attempt to set the record straight in his mind. (He has a journalist’s tenacity, often asking witnesses if they ever spoke to the police, and then regardless of their answer, revealing that he has their police statement right in front of him.) He is the witness of the film’s title, not present at the event itself, but willing to stand for his sister, to shine light on her vibrant and rich existence (and, in a particularly moving section of the film, her secrets) to reclaim her from the cold register of history and return her, in some way, to life.

The center of the film, however, remains Bill Genovese, who narrates and drives the action as he pieces together the truth, which is not so simple a thing as the ‘facts.’ He doesn’t only want to know what happened, but why, and even how. Confined to a wheelchair due to his war injuries, Genovese is a nonetheless imposing figure as he confronts reporters, lawyers, and even the aging witnesses in an attempt to set the record straight in his mind. (He has a journalist’s tenacity, often asking witnesses if they ever spoke to the police, and then regardless of their answer, revealing that he has their police statement right in front of him.) He is the witness of the film’s title, not present at the event itself, but willing to stand for his sister, to shine light on her vibrant and rich existence (and, in a particularly moving section of the film, her secrets) to reclaim her from the cold register of history and return her, in some way, to life.